Our Town’s Railroad Days Are Long Gone But Memories Remain – If You Know Where To Look

By Wade Stevenson, 1995

Former Historical Commission Member

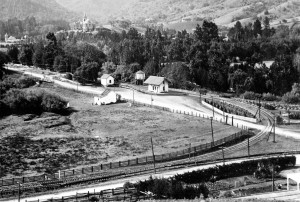

San Anselmo’s first depot, c. 1875. View is to the south from, approximately, the present-day intersection of Sir Francis Drake, Center Boulevard and Greenfield Avenue.

When the North Pacific Coast Railroad (NPC) began work on its line through Marin in the early 1870s, the county was sparsely populated, and the area which later became the town of San Anselmo consisted of a handful of houses scattered among ranches, farms, woodlands, and meadows.

The NPC constructed a narrow-gauge line which left Sausalito and followed the shoreline of the bay. A trestle carried the rails from Pine Point to Strawberry Point on the opposite side of Richardson’s Bay. The roadbed then traversed a steep hill and entered Corte Madera from the east. From there it ran northward through the Ross Valley to the key junction of San Anselmo. At San Anselmo the train branched into two lines: one heading eastward to San Rafael; the other traveling toward Tomales and then on to the commercially lucrative Sonoma County timber lands, with Cazadero as the endpoint. Ferry service was provided between Sausalito and San Francisco. The San Anselmo to San Rafael spur opened on July 25, 1874. A line to Tomales was operating the next year. Passengers could reach San Francisco from Junction – as San Anselmo was then called– in under an hour.

In the early years, San Anselmo was a key freight transfer point, a place for trains to take on water and fuel and a location for summer homes and vacation camps. Despite the promotional efforts of real estate developers and the railroad, the area maintained a decidedly rural character. Population growth was slow. From 1887 to 1890, San Francisco auctioneers Easton, Eldridge & Co. sold about 50 “villa sites” in the Sunnyside tract (Bolinas Avenue area), one of the earliest San Anselmo subdivisions. The railroad advertised the homesites in its stations and ferryboat cabins, and ran 25-cent round trip excursions to groups of potential buyers.

San Anselmo’s second depot, c. 1900

A picture of San Anselmo’s train station, circa 1900 (shown at right), taken from Red Hill, shows a depot, water tank, and freight shed clustered together on the east side of the creek, the three structures standing across the county road (now known as Sir Francis Drake Boulevard) from what would later become Bank Street and the First Bank of San Anselmo. A candy/grocery store operated at various times by Herman Zopf and Mrs. Mary Needham faces the station across the road. The Presbyterian Seminary looms in the background. No other buildings are discernible. This was San Anselmo’s second train depot.

The first station, a lonely outpost, had been located closer to the Hub which by 1900 was populated with gravel bins, a freight shed, a corral and horse barn, and a section house.

The Electric Years

By the turn of the century, the narrow-gauge steam trains had seen better days. Timber to the north had played out. Passenger travel, particularly in West Marin, was an adventure. One of San Anselmo’s most prominent landowners and real estate developers, former Marin County Sheriff and Tax-Collector James Tunstead, suffered serious injuries when the rail car he was riding in fell from a trestle near Point Reyes on June 21, 1903. He was luckier than two fellow passengers who died in the accident.

In 1902, the NPC was purchased by electric utility pioneers John Martin and Eugene de Sabla, Jr., and renamed the North Shore Railroad. Tracks in southern Marin were converted to standard gauge; a high voltage transmission line was strung from the Sierra Nevada to a power station at Alto (across from Mill Valley); trains were powered by an electric third rail; and the railroad boasted sophisticated switching equipment.

This was the beginning of the inter-urban train-ferry service that would featured heavy rail cars and provide transportation for generations of commuters to the city. At first the rolling stock consisted of wooden rail cars adapted for electric service. Later, combination steel and aluminum cars were added to the line. Trains averaged 25 to 30 miles per hour, with top speeds on straightaways of 50-60 mph. For some years after electric interurban train service opened on October 17, 1903, the railroad continued to run narrow-gauge steam trains on the same route, necessitating the placement of a rail positioned between the standard gauge tracks.

In 1907 the railroad, now owned jointly by Southern Pacific and Santa Fe, was consolidated with other lines and reborn as the Northwestern Pacific Railroad.

Refugees from the Earthquake

The combination of reliable electric trains and the 1906 earthquake spurred development in San Anselmo. In the wake of the quake, some of the summer homes became permanent residences, campgrounds filled with refugees, new subdivision maps were drawn, and a real estate row formed across from the railroad track. With the prospect of permanent residents and a growing economy, the town incorporated in 1907 by a slim margin of 83 to 79. In 1908 the electric third rail was extended to Fairfax, and in 1913 its last extension reached Manor, just west of Fairfax.

During the electric era, San Anselmo maintained its prominence as a major junction on the system. Southbound rail cars entering San Anselmo from San Rafael and Manor would be coupled at the hub before heading down Ross Valley and across the tidal flats to Sausalito.

Northbound trains uncoupled at San Anselmo, with San Rafael trains heading down the “Miracle Mile” corridor, and Manor trains traveling toward Fairfax along what is now Center Boulevard. Trains ran every half-hour during the commute rush. A 1913 schedule shows a 58-minute commute from San Anselmo to San Francisco, including a 32-minute ferry ride: In it the No. 413 departed San Anselmo at 6:37 a.m. and arrived in Sausalito at 7:00 a.m.; there commuters hopped on a ferry which left Sausalito at 7:03 a.m. and docked in San Francisco at 7:35 a.m.

Lansdale Station was the first San Anselmo stop of southbound trains emanating from Manor. After Lansdale Station, the train proceeded to Yolanda Station, downtown San Anselmo, and Bolinas Avenue before heading toward Sausalito with stops at Ross, Kentfield, Escalle, Larkspur, Baltimore Park, Corte Madera, Chapman, Alto, Almonte and its Mill Valley connections, Manzanita, Waldo, and Pine. In the 1920s and 1930s, the railroad ran a “School Special” to and from Mill Valley’s Tamalpais High, picking up students throughout the Ross Valley.

The End of an Era

Highway development in Marin in the 1920s and 1930s, along with the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937, brought a quick end to interurban train-ferry service. By 1938 the railroad had asked the California Railroad Commission for permission to shut the system down. To many Marin residents, abandoning the railroad meant more than changing modes of transportation, it meant the end of a way of life.

In 1939, the Save the Trains and Ferries League, which counted prominent San Anselmo civic leader F.J. Crisp among its directors, published a leaflet addressed to “Fellow Commuters and Friends.” The leaflet read in part: “we do not need to remind you of all we may lose; of the advantages of rail and ferry service and all that it has meant to us; the friendships, the card games, the times to visit, read, relax, exercise, if you want to even to knit – all this will be lost, never to return.”

Schedule reductions and fair increases delayed abandonment, but the line officially closed in the early morning hours of March 1, 1941. On a wet and windy February 28th, 1941 saddened train lovers gave their electric interurban a proper sendoff.

Train historian Jack Farley described the final salute: “It [the train] stopped and was serenaded at every station. A lot of these guys, even some of the guys working on the train, had had a snootful.” During the 66 years and seven months that the railroad served San Anselmo the area grew from a junction in a field to small town U.S.A.

Today, there are a few clues that railroads once ran through town, in the neighborhood names – Yolanda Station and Lansdale Station – and the raised roadbed of, and high curbs along, Center Avenue, but most of San Anselmo’s train landmarks have long since disappeared.

The water tank which fed the old narrow gauge steam engines on their journey from Sausalito to Point Reyes Station and beyond was torn down in 1938. The San Anselmo Herald noted at the time: “Now the steam engines are gone from the Fairfax cut-off. The tracks to Point Reyes Station have been torn up. Only electric trains zip past the tank now – and electric trains don’t have to stop for water.”

When train service ended in early 1941, San Anselmo’s depot was converted to a bus station. Rails were torn up and train right-of-ways became part of the town’s road network. By the early 1960s, almost everything linking San Anselmo to its railroad past had been razed, including the train station across from Bank Street, and the switching tower (Tower No. 4) and Northwestern Pacific powerhouse building at the Hub.

For what had been a San Anselmo institution, it was an amazing disappearing act.