Celebrating 100 Years of Stories and Discovery

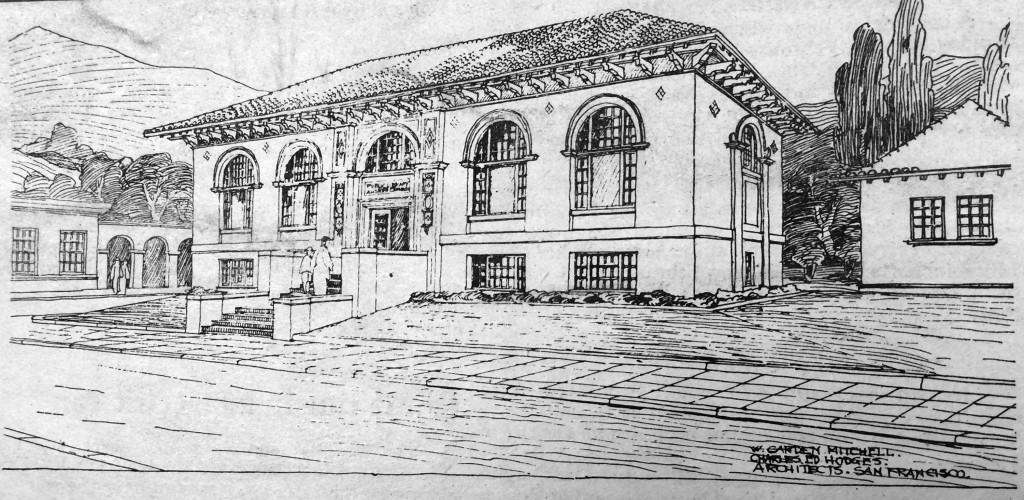

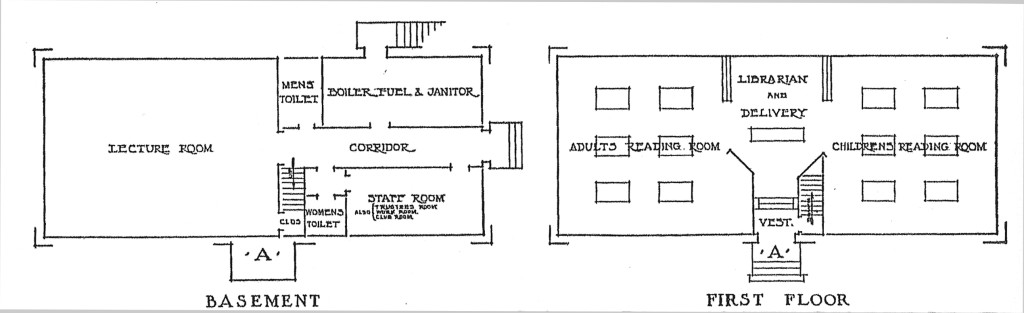

Architects’ drawing of San Anselmo Public Library, 1914

The San Anselmo Public Library celebrates its centennial in 2015. The library, constructed with funds from a grant from the Carnegie Corporation, was dedicated on the evening of February 12, 1915. The San Anselmo Herald reported:

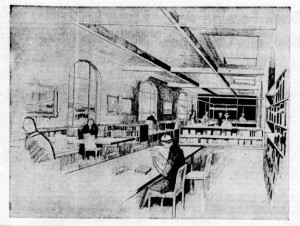

Enthusiasm marked the dedicatory services of the Public Library last Friday night. A typical gathering representing the best thought of the people of this progressive town showed by their attendance and happy greetings the real pleasure they felt in their new building. Few had seen the interior and were not therefore aware how completely the need of a reading public had been provided for. The big reading room facing the East the entire length of the building is perfect in lighting and furnishings. The shelves extend entirely around it save at the entrance and at the librarian’s desk. There is nothing bizarre about it but simplicity itself.

The San Anselmo Women’s Improvement Club was instrumental in the efforts to provide San Anselmo with a library. The club was formed in early 1912 with the goal of making San Anselmo a more desirable place to live. It started with 34 members each paying 10 cents per month in dues. A number of issues were immediately addressed – the need for a mailbox at the depot, the quality of movies presented at the San Anselmo Theatre, the planting of trees along the streets and filling in mosquito-breeding marshes. Within six months, the club turned its attention to the building of a public library for the town and formed a library committee. During this period, women’s clubs all over the United States worked to develop libraries for their communities, and it is estimated that up to 75% of the libraries across the country came to be through the efforts of individual women or women’s clubs.

Emma Gruber Foley (Mrs. Thomas F.), Letitia Barsotti Jones (Mrs. Ottiwell) and Jennie Stoops Clemenson (Mrs. Newton E.) were very active members in the club and library committee. Emma Foley served as president of the club and was remembered by a large group of friends at her 1945 funeral service for her charitable and kindly acts. Letitia Jones was honored posthumously in 1961 for her 38 years of service on the Library Board.

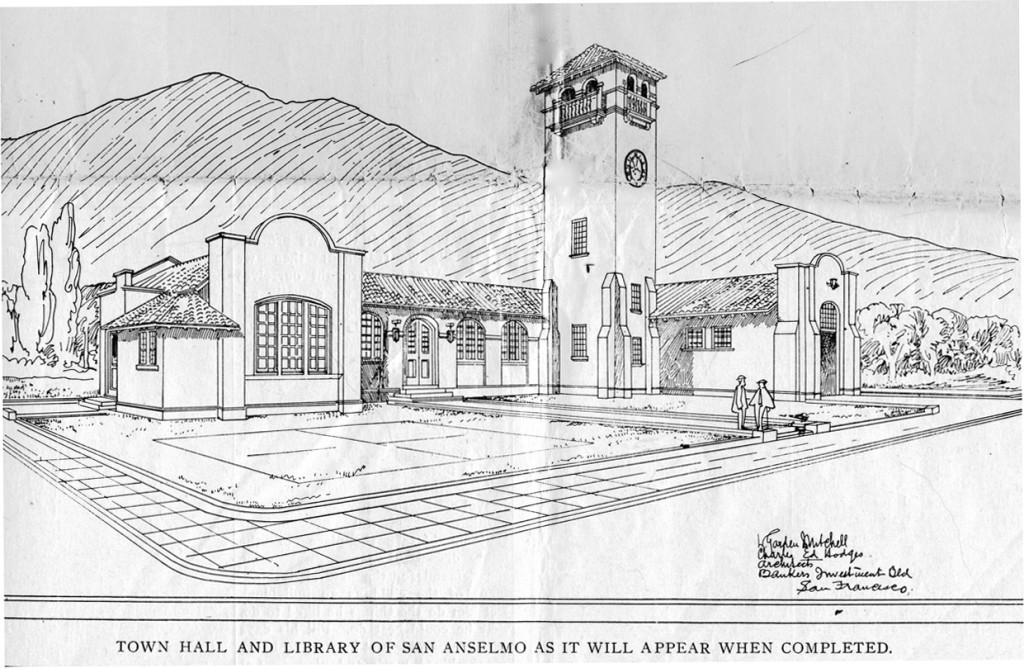

The San Anselmo women, thinking the town was too small to qualify for a Carnegie grant, set out to raise money on their own by holding card parties, bazaars and bake sales. They eventually raised $600 and suggested that a room for a library be built behind the council chambers. The plan was presented to the Town Trustees for approval in July 1912, and architects Mitchell & Hodges drew the plans.

Architects’ drawing of proposed room addition (left)

However before this room construction was undertaken, Prof. Thomas Day of San Francisco Theological Seminary suggested that it might be possible to get money from Mr. Andrew Carnegie. A letter to the Carnegie Corporation Trustees was drafted by the town clerk asking for $6,000 and advice was sought from Judge William Morrow, serving on the U.S. District Court of Appeals in San Francisco.

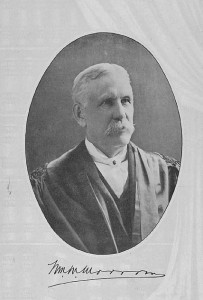

Judge William Morrow

Judge Morrow had been instrumental in helping San Rafael secure a grant. He was a trustee of the Washington-based Carnegie Institution, and through this was personally acquainted with Andrew Carnegie. Morrow willingly offered assistance, and the town was awarded $10,000 for a library building in January 1914.

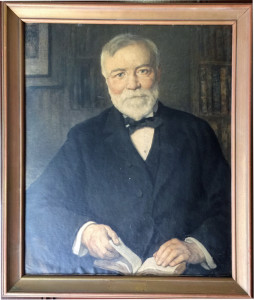

Portrait of Andrew Carnegie received in 1935 in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of his birth

Between 1886 and 1919, Andrew Carnegie’s donations of over $40 million paid for 1,679 library buildings in 1,419 communities across America. San Rafael (1904) and Mill Valley (1910) successfully applied, and San Anselmo became the last Marin community to receive a grant. The grant application process was rather straightforward and the money was readily granted, but conditions were also placed on the gifts. Communities had to own the building site and to agree to maintain the building at an amount equal to 10% of the gift annually.

San Anselmo Town Trustees passed a resolution April 27, 1914 accepting the grant and its terms. The town-owned parcel of land, donated by James Tunstead, next to the new Town Hall was eventually selected as the site though other sites were suggested and rejected either because dangerous railroad tracks had to be crossed or they were too far from the center of town. Town Hall architects Mitchell & Hodges designed the building in the Spanish Revival style. The correspondence between the architects and the Carnegie Corporation are lacking in the town’s historical records, but Lucy Kortum of Sonoma wrote in her 1990 thesis, Carnegie Library Development in California and the Architecture it Produced 1899-1921, that “Carnegie secretary James Bertram objected to their plans as lacking a basement and being too narrow a rectangle. Hodges defended the shape and resisted lowering on the grounds of possible contamination from sewage, but he eventually agreed to raise the site so that the basement could be recessed four feet.”

The building seems to have closely conformed to Plan A in the notes and drawings that James Bertram compiled in his “Notes on the Erection of Library Buildings” with its one story rectangle with a central entrance, a single large reading room with shelves around the perimeter, a basement with lecture hall, staff room, heating and toilets. Bertram’s ideal was also one in which a single librarian could oversee the entire room.

Bertram’s Plan A

Fred H. Field of Ross was the contractor. He was the lowest of ten bidders and completed the work in less than 125 days. He was assisted by subcontractors Frederick Kinsella, Ray Bowley, James Elliott and William Dwyer. The main reading room, with oak flooring and trim, had space for 8,000 with approximately 1,000 donated books on the shelves on opening day.

The basement’s 120 seat Carnegie Lecture Room was available on a rental basis to local groups. The heat for the building was generated by hot water; this is still the case today.

The San Anselmo Library Board meeting minutes and annual reports indicate that the building was well maintained given a limited budget. Doors were replaced, interior and exterior walls received periodic coats of paint, the wood floors were eventually covered with “battleship linoleum,” the old coal furnace was converted to gas, landscaping was installed and drainage issues were addressed. Fire Chief Charles Cartwright was paid $30 a month for janitorial and maintenance services.

In May 1937, the Town Trustees requested that Library Hall in the basement be converted into police headquarters. The Library Board secretary dutifully wrote to the Carnegie Corporation about the matter and received this prompt reply: “It must be realized that a request was made for a library building, and relying on the good faith of the community, money was provided for a Free Public Library Building. The large room in the basement of these buildings was intended to be used for supplementing library work by lectures, study clubs, etc. For the police department to use the room as its headquarters would, it seems to us, be contrary to the original understanding.”

By 1955 the library had outgrown its quarters, and the Library Board requested that Town Council consider adding a new wing. Nothing happened until the Board pushed the matter again in June 1957. The town budget was the issue, and it wasn’t until early 1959 that plans were drawn by architects Adrian H. Malone and Roger F. Hooper to expand the library by 1,400 sq. ft. over the parking lot behind and convert the reading room into additional stacks.

What has always been referred to as the “1960 remodel” was actually delayed due to budget issues until 1961. In May of that year, the library closed for six weeks so the work, estimated at $54,000, could progress.

Architects’ drawing of addition to the Library, 1959

The flat roof addition, described as “modern concrete and glass,” added much need space, and since it wasn’t visible from the front, it didn’t impact the exterior historical character of the building. On the interior though, linoleum tiles were installed to match those in the addition, and the wood frame windows and doors were replaced with aluminum ones.

Another remodel was completed in September 1973, after a two month closure, in which the back office and workroom were shifted to the front of the building. The elevator on the northwest corner was added in 1979 providing building access to the disabled for the first time, and a room was configured for a historical museum on the lower level.

The seismic safety of the building was seriously questioned in a 1984 report, and the fate of the library building was heavily debated and analyzed during the years that followed. A 1986 legislative mandate regarding unreinforced masonry buildings pushed the issue further. The 1987 “Report on the Future Use of the Present Library Building” by an appointed planning committee addressed the issues: “Should we attempt to preserve this inadequate, unsafe relic, or should we destroy what has become historically precious and try to provide a library that would meet the needs of a progressive well-educated community?” The committee urged council to demolish the building and construct a new facility, but the council disagreed and decided in May 1989 that the building should be repaired and continue to provide library services while preserving the historical appearance. Funding was an obstacle to the start of any work as the Town’s application for funds under the California Library Bond Act of 1988 was unsuccessful. The October 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake made the seismic work even more urgent.

Dan Peterson & Associates were engaged in 1992 to prepare a plan and complete the necessary studies and drawing. The construction project was undertaken in two phases. Phase I started in 1994 and included the seismic upgrade that anchored the masonry walls to the roof, moisture proofing, electrical upgrades and restoration of the historical interior and exterior. The library only closed for one or two weeks as the staff shuffled from one side of the floor to the other as the work progressed. Phase I work was completed after the original contractor was fired and replaced.

Phase II of the project almost didn’t happen. Measure G, to finance improvements to streets, storm drains and the library building, lost by 24 votes in November 1994. Quickly re-introduced, Measure G then passed by a margin of 32 votes in June 1995 and the work proceeded. Phase II focused on bringing the building into compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and included building a ramp to connect the upper and lower floors, linking the library with Town Hall via a gallery with historical displays and reconfiguration of space for the historical museum and Friends of the Library work space. Flood gates were also installed.

A grand party was held April 26, 1997 to celebrate the completion of the long San Anselmo Library rehabilitation and renovation project.