The Story of Mr. Montgomery And His Chapel

By Michael Peterson, 1995

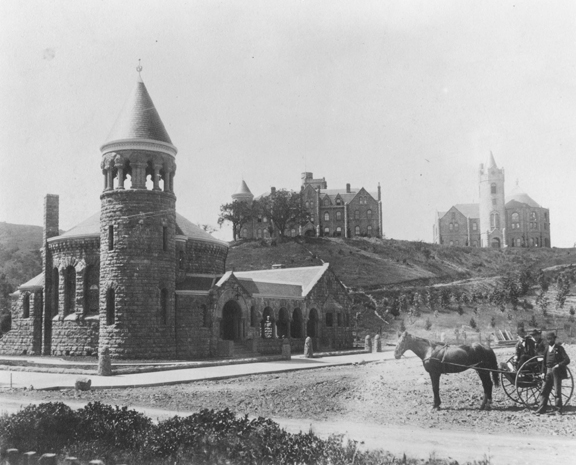

Montgomery Chapel

“The Hookooeko of Nicasio and Tomales Bay say: ‘When a person dies his Wal’-le or Ghost goes to Hel’wah the West, crossing the great ocean to Oo-ta-yo’-me, the Village of the Dead. In making this long journey it follows hinnan mooka, the path of the Wind. Sometimes Ghosts come back and dance in the roundhouse; sometimes people hear them dancing inside but never see them.’ ” [1]

When Alexander Montgomery died at the age of 68 on November 4, 1893, his memorial and final resting place on the campus of San Francisco Theological Seminary in San Anselmo was still a dream.

Four years earlier, on December 2, 1889, the moneyed Montgomery had written a check for $250,000 that in 1892 paid for the construction of Montgomery and Scott halls, plus a faculty dwelling on Bolinas Avenue. Later, in June 1891, he gave an additional $10,000 for two more faculty dwellings. In his will, Montgomery bequeathed to the Seminary what amounted to another $175,000 – and yet the total of all the money donated constituted a fraction of his wealth, for at his death the estate was estimated to be worth over two million dollars.

In the sixth clause of the will, Montgomery bequeathed $50,000 in trust to W.F. Goad and A.W. Foster, his executors, “for the purpose of erecting and taking care of a monument on the grounds …” of the Seminary. “A vault shall be placed therein for the reception of my body after my death, where I desire my body to be interred. I desire and direct my trustees to use their own judgment in the erection of the same.” [2]

Goad and Foster did use their judgment in establishing Montgomery’s monument: the result is the handsome, recently restored Montgomery Chapel on the corner of Bolinas Avenue and Richmond Road.

Montgomery, Foster, and Goad made the decision to make the memorial in the form of a chapel in February 1893, when the will was executed. It is not clear exactly when construction began or just how specific Montgomery was about the design. A legal document [from 1898] states that, “after the making of the will … and before his death, … Montgomery, with the consent and approval of the … Theological Seminary did himself proceed to erect and did actually commence the erection and construction upon the … grounds … of the … Seminary of the monument referred to in the … will, and which … monument was in the form of a memorial chapel ….”

A Chapel of a Different Sort

The chapel is something of an anomaly for a Presbyterian seminary because it exhibits no Christian elements or symbols. Instead, the stained glass windows and stone carvings contain images more or less suggestive of the Old Testament; and, to top it all off, the bell tower is crowned with a strange orb rather than a cross. These unusual symbols would have strong appeal to men steeped in the lore of Freemasonry, as were Montgomery, Foster, and Goad.

Montgomery was a Presbyterian in sympathy only. At Montgomery’s funeral, held in the Golden Gate Hall under the auspices of the Pacific Masonic Lodge, the Rev. W.B. Noble pointed out in his eulogy: “He was not a churchman, though his Scotch ancestry was, of course, Presbyterian. It was the faith of his fathers, and he loved it. That he was not a professing Christian we regret, but who can tell what communings were held in the inner temple of his soul ….”

Montgomery’s remains were interred at Laurel Hill, San Francisco, in November 1893 and were not transferred to the Seminary Chapel until April 22, 1897 – almost three and a half years later. The cornerstone was laid on April 26, 1894, almost seven months after Montgomery’s demise, even though work had already commenced on the project before his death. Something had happened to inhibit progress. Montgomery Hall, Scott Hall, and the three faculty houses all together had taken less than a year to complete and required a good deal more effort.

Why would an important edifice begun sometime before Montgomery’s death take so many years to complete? And why was Mr. Montgomery kept waiting so long in the cold ground of San Francisco?

One factor that slowed the construction process was a lack of immediately available funds. The court’s distribution decree for the funding was not issued until May 15, 1895 – over a year and a half after the death. Then, even after the money was available, work on the chapel did not begin until May 1896, a full year after the court decree. Once the work was commenced in earnest, it was completed the following May.

Montgomery’s Clouded Past

One explanation of the time lapse may be bound up in Montgomery’s clouded past. Born in Northern Ireland in 1825, into the family of a small tenant farmer, he received almost no formal education. He was apprenticed to a tailor and sustained himself in that trade in England and, in 1846, New York.

By late 1848 he was haunted by the discovery of gold in California. He sold everything and sailed for San Francisco on January 24, 1849, not reaching his destination until seven months later on September 6. He was almost too late to be a 49er. From San Francisco he continued on to Sacramento and beyond to Bidwell’s Bar on the Feather River, where he promptly became seriously ill with scurvy.

By 1851 he was sick of gold mining and took a turn at wagon hauling between Sacramento and Bidwell’s Bar. By the spring he was back in the clothing business, eventually settling in Benicia. Next he tried running a stage line between Benicia and Napa City, but that venture did not start turning a profit until he settled on running bowling alleys and a boarding house in Sacramento. He discovered his real calling when he lent $5,000 to a Judge Wilson and thus became actively involved in the money-lending business.

In 1855, now thriving, he settled in Colusa, remaining there until the 1880s. In Colusa he became a full-time money lender, usually lending on land with a mortgage as security. The wheat farmers in Colusa and Tehama counties were ripe for the picking. They were willing to give good security in mortgages on property and to pay a high rate of interest for loans. Montgomery was a millionaire by the time he reached Colusa.

Shotgun Marriage and a Family Feud

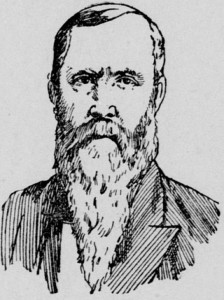

Alexander Montgomery

In Colusa he met Elizabeth Green, she 17 and he in his early 50s. By 1883 the couple had two daughters and were living in Oakland. On August 28, 1884, Montgomery, incapacitated by one of his whiskey binges and comforted by one of his young daughters, became an unsuspecting participant in a shotgun wedding. Lizzie Green’s mother and sisters could bear Lizzie’s predicament no longer and came bursting into Montgomery’s room armed with two pistols (or so claimed Montgomery) and with one Rev. Francis Horton to perform the impromptu service.

Despite the whiskey, he would not take the insult lying down. In November, Montgomery had the Green family in court to annul the pistol marriage, and annulled it was the following April. In the meantime, he purchased General Vallejo’s mansion on the corner of Leavenworth and Vallejo in San Francisco. On April 15, 1885, just days after the annulment was final, he and Lizzie were married by common consent at the Grand Hotel in the City. Montgomery’s complaint about the pistol marriage was that he had not been given a choice. He did in fact care for Lizzie and their children.

There is a Green family tradition indicating that the bitterness between Montgomery and his in-laws did not end with the common-consent marriage. According to a son of one of Lizzie’s sisters, Lizzie told him that she, Montgomery, and their lawyer, Arthur Rodgers, had conspired to defraud Mrs. Green of about a half-million dollars, leaving her to die destitute in 1906. The nephew contended that Mrs. Green’s treatment was in revenge for her part in the pistol marriage. According to the nephew, Montgomery “was a shrewd, crafty, cunning money lender and land speculator of great wealth … In the reflected light of his gold are the terror stricken faces of this shrewd, rapacious money lender’s victims.”

Montgomery Chapel, 1920s

A bitter statement, indeed. If there is any grain of truth in the nephew’s tale – more than a tale because his words were part of formal charges brought in a legal suit – then the blessings Montgomery bestowed on the Seminary were mixed. And was Lizzie present to advocate the wishes of her late husband to expedite the chapel construction and the transfer of his remains? Not with much diligence: Her designs lay elsewhere. In good time she entered into marriage with Arthur Rodgers, the attorney. And the body of Alexander Montgomery decayed in its cold San Francisco plot for three-and-a-half years.

As you pass Montgomery Chapel sometime late at night, remember the Miwok story and listen for the ghost dancing in his private roundhouse. The dance you hear could be the shuffling steps of a soul twisting slowly in sorrow.

Michael Peterson is a former San Anselmo Historical Commission member.

NOTES [1] C. Hart Merriam, collector and editor, The Dawn of the World: Myths and Weird Tales Told by the Mewan Indians of California (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1910), 217.

[2] Quoted from Montgomery’s will.